Git Good

Git is a free and open source distributed Version Control System (VCS). Git can be hard, especially for people discovering it for the first time, but there are a lot of things that make this an exceptional VCS worth learning. This post is not meant to be a git tutorial, but rather a compilation of things and tips I find interesting. I also wanted to give a perspective of git independent of services like GitHub. Hopefully you can find something useful and “git better at it” 🙃.

If you’re looking to learn how to use git, take a look at the Pro Git book, it’s free and it is a great resource!

Git is not GitHub 😮

Services like GitHub made git particularly popular, but the convenience of something like Github has its downsides for new users: it causes confusion about the differences between GitHub or GitLab, and the actual version control system, git. While the former are great to host git repositories and make them publicly available (among other things), git is a piece of software designed to allow for distributed version control and collaboration. This means that you can use it offline, without GitHub, you can collaborate with people via chat, email, and anything that allows you to send text to someone else. Yes, GitHub makes it convenient to host your project and make it discoverable; it provides an incentive for collaboration, but, at the end of the day, GitHub is not git, just as Gmail is not e-mail.

Git is distributed 🖧

For those used to GitHub, collaborating with git over e-mail might seem anachronistic, but, consider the scale of projects and what git was designed to do. Being able to send contributions as plain text allied with the threaded nature of e-mail, means that you can have multiple discussions around certain aspects of a contribution, which is a big plus. Linux kernel development, for example, doesn’t happen on GitHub or GitLab. From the linux kernel GitHub Pull requests (GitHub’s system for submitting contributions):

Thanks for your contribution to the Linux kernel!

Linux kernel development happens on mailing lists, rather than on GitHub - this GitHub repository is a read-only mirror that isn’t used for accepting contributions. So that your change can become part of Linux, please email it to us as a patch.

Sending patches isn’t quite as simple as sending a pull request, but fortunately it is a well documented process.

Here’s what to do:

- Format your contribution according to kernel requirements

- Decide who to send your contribution to

- Set up your system to send your contribution as an email

- Send your contribution and wait for feedback

The development happens on various mailing lists for multiple subsystems. It’s distributed development to an unprecedented scale. This scale has a price, discipline in your contributions, something that GitHub doesn’t really help reinforce –which seems to be the whole issue that the creator of git Linus Torvalds has with it.

Git daemon 🌐

Focusing the development on a centralised service like GitHub can feel like

you’re using an improved version of Subversion client/server approach, but

remember, git is truly a decentralized system and we can do better. Suppose you

don’t want to use GitHub, but want to make your repository available for other

people to clone, pull from, etc. Git supports Peer-to-Peer setup out of the box

with git

daemon.

Collaboration then happens on each peer local copy of the source tree and some

form of communication channel (e.g. e-mail, chat, etc).

From your git folder you can execute the following command

git daemon --export-all --base-path=. --reuseaddr

-

--enable=upload-pack: (enabled by default) allows forgit fetch,git pull, andgit clone. -

--export-all: means that you don’t have to create a file named git-daemon-export-ok in each exported repository. -

--base-path: allows people to clone projects without specifying the entire path. Example: if you start the daemon with--base-path=/srv/gitand try to pull fromgit://example.com/hello.git, git daemon will interpret the path as/srv/git/hello.git. -

--reuseaddr: allows the server to restart without waiting for old connections to time out.

Congratulations, your machine is now running a git server and anyone can do:

git clone git://192.168.1.42/ #Your IP

# or

git remote add Foo git://192.168.1.42/

git fetch Foo

git checkout develop

git push Foo develop

Git patches 📝

As we have discussed, git is a decentralized system, you can send contributions to anyone without the need of a centralized git repository. This is not only the default way of collaborating with git, it is particularly useful when a server is down, or if you don’t have permissions to write to a remote repository —but would still like to propose changes.

You can create a patch from your current changes without committing the code on your source tree:

# changes in the working tree not yet staged for commit

git diff > big-improvements.patch

# or changes between the index and your last commit;

# what you would be committing if you run "git commit"

# without "-a" option.

git diff --cached > big-improvements.patch

As an example suppose the change is the addition of a README file, the diff would look like this:

diff --git a/README b/README

new file mode 100644

index 0000000..e69de29

More often, what we would like to do is to propose a change we have made in your

local source tree. To do this, we can use the git

format-patch command:

git format-patch master

if we have commits ahead of the master branch, a diff file will be generated. We can also reference other commits in the same branch. Suppose we made changes in the current branch and want to reference the changes in relation to the last commit. We can do:

git format-patch HEAD~1

the patch file will contain something like:

From daf1010eb425a67ca6b0ba60f7cbec15bcff31f1 Mon Sep 17 00:00:00 2001

From: John Doe <heresjohnny@bestmail.com>

Date: Tue, 09 Sep 2020 15:42:00 +0100

Subject: [PATCH] Update README

---

README | 1 +

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

diff --git a/README b/README

index e69de29..d0fc019 100644

--- a/README

+++ b/README

@@ -0,0 +1 @@

+This is a README file, that is all.

--

2.28.0

to apply the patch we do:

# patch as unstaged changes in your branch

git apply 0001-Update-README.patch

# patch as commits

git am 0001-Update-README.patch

For more information, check the documentation for git

diff, git

format-patch, git

apply, and git

am.

Git tips 🔥

We are all bound to get stuck sometimes when things go wrong. A good starting point is this compilation. These are solutions to problems I often have to solve.

Premature commit 🔧

You pulled the trigger too fast on that commit and wish you could include

additional changes? Make your changes, call git commit --amend and done. (Also

useful to change the commit message.)

Go back ⌛

We messed up, go back to a previous commit.

# go back n commits n=1 in this case,

# --soft: optionally don't discard changes

# and put them on the staging area instead

git reset HEAD~1 --soft

Put changes on hold 🚧

So you want to get back to the state before you started making changes, but don’t want to throw these changes away:

# stash the changes

git stash

# get the changes back when needed

git stash pop

Where it went wrong 🔍

You have a problem and don’t know which commit introduced it, enter git bisect:

git bisect start # start a bisect section

git bisect bad # Current version is bad

git bisect good v2.2.1 # v2.2.1 is known to be good

bisect will now choose commits in the middle of the history and you can mark

them as good or bad with the same commands. When no more revisions are available

you’ll have a description of the commit that caused the problem. You can then reset

the bisect state with git bisect reset.

Rebasing commits 💥

Sometimes we make two commits when in reality, we could have included all the

changes in a single commit, and our history would be clearer. This is what is

known as squashing. We can use git rebase to meld commits with previous

commits. It can also be used instead of merging branches. Git’s rebase command

temporarily rewinds the commits on your current branch, pulls in the commits

from the other reference and reapplies the re-winded commits back on top.

Most people will advise you to always squash the commits and rebase them onto the parent branch (like master or develop) before you submit a pull request or send out a patch. Whether rebasing is preferred to merging really depends on the context.

If you want to read more about rebase vs merge, check out this

post

Whatever you do DO NOT rebase commits in a upstream repository people can pull from. It will mess everyone’s history and lead to conflicts that all downstream peers will need to fix. Also, it’s never a good idea to rebase somebody else’s work, see this discussion.

# rebase last 2 commits

git rebase -i HEAD~2

The interactive system will open an editor where you can choose each commit in a list that are about to be changed. In this case, it will list 2 lines with the last 2 commits. This list reflects exactly how your branch will look like after the rebase:

pick c8175df added line

pick dc58443 added final line

# Rebase 65e38e0..dc58443 onto 65e38e0 (2 commands)

#

# Commands:

# p, pick <commit> = use commit

# r, reword <commit> = use commit, but edit the commit message

# r, reword <commit> = use commit, but edit the commit message

# s, squash <commit> = meld into previous commit

# f, fixup <commit> = like "squash", but discard log message

# ...

You can pick, reorder or squash any commits you want to make for a more readable history.

As we discussed, you can also rebase the current branch onto another

git checkout feature

git rebase -i master

For more information about rebase see the documentation

Good commit messages 🧐

Commit messages should be consistent across a project in terms of style, content, and metadata. But some good rules are as follows:

- the minimum is a single short descriptive line (e.g. less than 50 characters);

- separate subject, body, other data, with blank lines;

- include metadata such as references to commits that introduce problems being solved.

- wrap the body to 72 characters.

A good one liner can be something like this

Fix typos in the abstract

the form <Verb> <Target> <Description> is sometimes enough context to describe

a simple change.

A great way to learn what good commit messages look like is to study repositories where this is done right. It is to no surprise that the Linux kernel and git itself are good examples. There are also plenty resources on the subject such as How to Write a Git Commit Message.

Good commit messages are an important collaboration tool. They are the best way

to communicate context about a change to a fellow developer, or to our future

selves. git diff will tell us what changed, the WHAT, but this added context

documents the WHY.

Git for writing 👨💻

I have been experimenting with git for writing. The idea being that we can benefit from using version control with our papers, lecture notes, blog posts, etc. Suppose we are considering git to track changes in a scientific paper. We can mark submissions with tags, use patches to incorporate changes from collaborators, branches to work on revisions, git diff to visualize the changes, etc.

Remember that git cares about meaningful lines, so the first thing to take into account is that we should, at minimum hard wrap our lines at a given character limit, and/or write each sentence on a different line. By using Markdown or LaTex to write a document, we will be tempted to use the editor for soft word wrapping. This can lead to huge one-line paragraphs. The problem with this is that changing a word in that paragraph will be recorded as a change to the entire paragraph. Moving lines around has a similar effect.

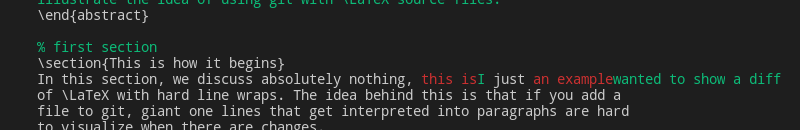

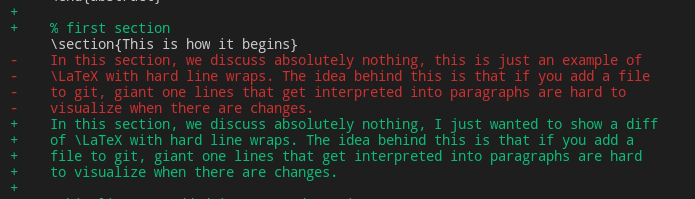

As a workaround, to visualise changes in such cases, we can use the

--color-words option with git diff.

Consider a LaTeX document, for example. If we move lines around and call the following command:

git diff --color-words

this is what we get:

But what is actually recorded in the diff is the following:

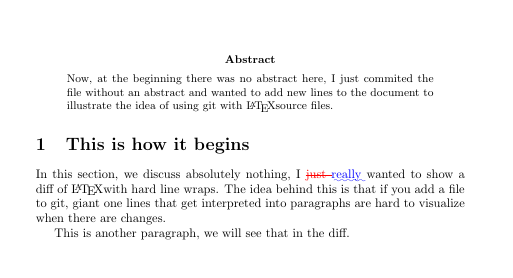

To generate a pdf to visualise the changes in our tracked latex document, check out the git latexdiff tool that wraps around git and latexdiff.

The result of the following command is an output pdf with the changes in relation with the previous commit

git latexdiff HEAD~1

Archiving projects 🏛️

This is not related to git specifically, but more with good open science practices. Online repository hosts like Github are not archival. Git itself lets us tag commits to mark versions and releases, but tags can be deleted, and storage is totally dependent on us. Remember, git distributed, and local. Git is meant to track changes and collaborate, not archive the state of projects.

Platforms like Zenodo, on the other hand, let you conveniently archive versions of GitHub repositories based on GitHub releases (tags).

If you already use GitHub as a public accessible mirror for your project tracked by git, this means you can easily archive certain versions of your project and automatically make them citable since Zenodo attributes a Digital Object Identifier (DOI) to its submissions.

With this said, we should discuss how to archive, backup, or share your entire git repository without depending on any specific platform. There are a couple of options.

You could zip it but… 🗄️

A zip of your project folder will include EVERYTHING, yes, including your .git

folder with all the changes, branches,

reflogs but this might not be what you

actually want. A zip of the project folder will include untracked files, and

you could accidentally share sensitive information, irrelevant temporary files

or IDE and editor configuration folders, etc.

Mirror clone 🔗

A git clone with the option --mirror creates a bare repository (which contains

only the stuff in the .git directory) and it maps all refs (including

remote-tracking branches, etc.) to the target repository. This means that these

refs can be updated by a git remote update.

git clone --mirror myrepo repo.git

# or some remote repository

git clone --mirror https://github.com/davidenunes/repo repo.git

You could make a backup of your repository by creating a mirror (bare) repository and archive it.

To restore the bare repository, you can do the following:

mkdir myrepo

mv repo.git myrepo/.git

cd myrepo

git init

git checkout -f

If you want to refresh the backup you just need to call git remote update from the clone location.

Bundling 📦

Git is capable of bundling

its data into a single binary file. You need to list out every reference or

specific range of commits that you want to be included. If you intend for this

to be cloned somewhere else, you should add HEAD as a reference as well.

Alternatively, you can use --all to include all refs.

Within the project folder do:

# this will include all info to recreate the master branch

git bundle create repo.bundle HEAD master

# optionally --all for all refs to be included

git bundle create repo.bundle --all

You can then send or store this file, and in another machine unbundle it into a repository:

git clone -b master repo.bundle repo

If you don’t include the HEAD reference (or --all) you will get the

following error:warning: remote HEAD refers to non-existent ref, unable to

checkout.

Using --all makes your bundle file match what you would get with git clone

--mirror

Thank You

Thank you for reading ❤️ I would love to know what you think, if you do things differently, or have any other neat tips / suggestions. Let me know in the comment section. You can also follow me on Twitter, or subscribe to the RSS feed for more content.

Comments